Beauty and the beast

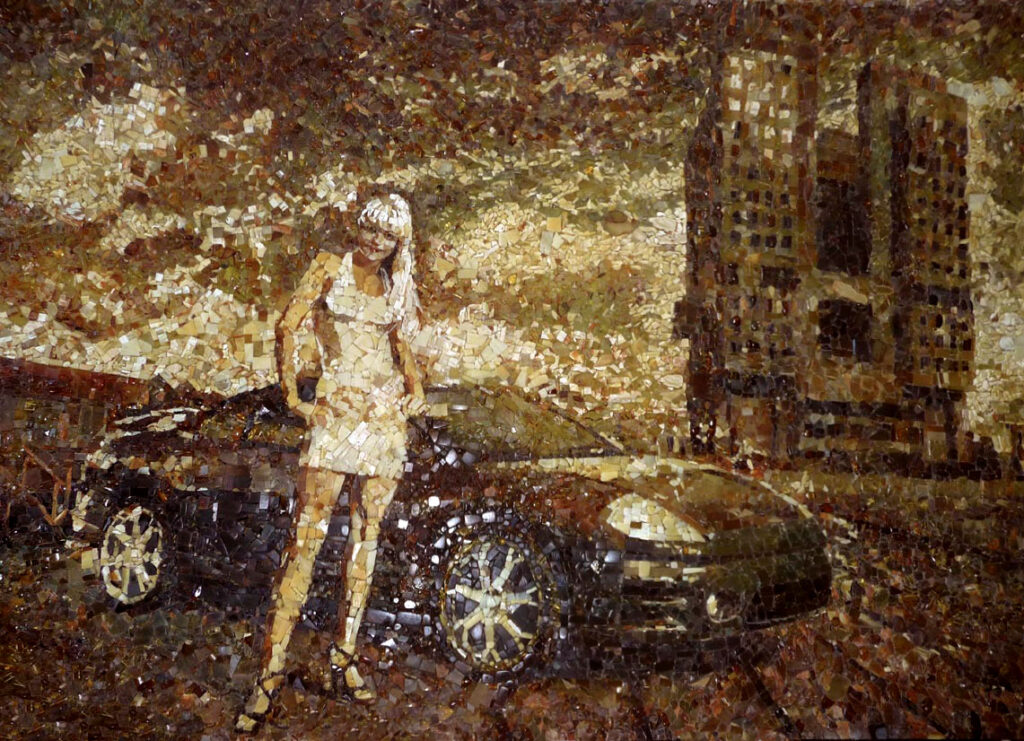

Amber Mosaic, 230x133x 20cm, Kaliningrad, Moscow 2009

Kaliningrad, formerly known as Königsberg, is a Russian exclave on the Baltic Sea, surrounded by European countries. When EMPFANGSHALLE visited the city in 2009, the silhouette of the old Königsberg adorned numerous walls, which was largely destroyed during World War II. In many conversations with the residents, the question of Kaliningrad’s identity was addressed. Are they wholeheartedly Russian? Or rather, Königsbergers? And how do modern Kaliningraders express themselves? Amidst the socialist buildings, there was an ambivalent longing for the past beauty of the historical city.

In 1967, the ruins of the castle were demolished to make way for a 16-story high-rise, the “Dom Sowetow,” the House of Soviets. Due to structural problems, it remained a construction ruin and is therefore colloquially known as “The Monster.” Rumors have it that the lost Amber Room is buried underneath. Amber still holds great significance in Kaliningrad today, as the world’s largest deposits are extracted from the Baltic Sea sands.

EMPFANGSHALLE offers the “missing mosaic piece” for the city’s ever-changing identity. They created an image from their impressions on-site, combining motifs from a mythical story. Thus, a mosaic featuring the Amber Queen of Kaliningrad in front of the Dom Sowetow was born, executed by local artisans as perhaps the largest amber mosaic ever made there. A queen, a sunken castle, a lost treasure, and a monster – these are the ingredients from which identity-forming stories are forged, from Greek myths to “Game of Thrones.”

The project took place within the framework of “Art on Site” with the NCCA Moscow and the Goethe-Institut. The artwork was exhibited at the local Amber Museum as well as at the 3rd Moscow Biennale.”

Interview with the artists’ group “Empfangshalle”

What were your impressions of Kaliningrad? Were they different from those of your first trip?

One’s first impressions are the most important ones. One’s opportunity to see a city objectively lasts only the first three days, after that, one is no longer fresh. That is why our first trip was also the most intensive phase of our work. We talked for hours at a time about everything we had seen. We felt like treasure hunters – and that also influenced our choice of material: costly amber. How did you structure your project work? Our project work was like collecting pieces of an amber mosaic: matching each individual piece of amber with the next one, searching for the piece that fits. This is just how we gathered our impressions and sought to put together a complete picture with them. We quickly realized that the image of the House of the Soviets and the history of the place where it was built were important to us, as it is a genuine symbol of this history: nobody lives in it, but still it exists, and the city and its inhabitants have to think about what they want to do with it, and how to live with it.

In your view, is history the most important issue in Kaliningrad?

History is still an open wound in Kaliningrad. Both the war and the post-war years live on in the flesh and blood of the city to this day. It is as though people cannot relate to their city even now. So many layers of history are mixed together here. First, there is the old Koenigsberg, a very important image for the city’s people. The Russian population feels drawn to their old roots in Koenigsberg. The Soviet era comes next, during which what was left of the Old City was destroyed and the new one was built. The third layer is the present, with its pursuit of everything new, with advertising, with its brilliance and dynamism. And we asked ourselves: what might the symbol of a modern Koenigsberg be? If we bought a postcard of Kaliningrad as a souvenir, what would it show? We decided to create our very own, personal souvenir of Kaliningrad. We took amber from the city’s history, the House of the Soviets from the Soviet period, and we asked the Kaliningraders themselves about the present. Why did the image of a girl and a car become the answer to this question? Most Kaliningraders find the House of the Soviets monstrous and an eyesore – totally unsuitable as a symbol of their city. We therefore asked ourselves about beauty and ugliness: what Beauty might be contraposed to what is monstrous in the eyes of the inhabitants, to their Beast? We therefore began to investigate the Kaliningraders’ ideas about beauty. Beauty is very important to people here. Women invest huge amounts of time, money and energy in their appearance, and men in the beauty of their cars. One sees fashion shows wherever one goes, in every café there is a TV showing fashion shows. We had never seen anything like it! So our Beast, the House of the Soviets, was unthinkable without its Beauty. What we like about this idea are the contrasts between past and present, of lifelessness and vitality, what the city’s people find ugly or beautiful. But maybe things are more complicated than that, and in this situation one can never say exactly who is Beauty and who the Beast.

Art on Site, NCCA Moscow and Goetheinstitut, 3. Moscow Biennale, Russia